ACH - XZ Backdoor

James, 18 April 2025

Who Was Behind the XZ Backdoor? A Threat Attribution Exercise Using ACH Recently in class, Alex (classmate) and I worked on a threat attribution excersice using the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) method. The focus? One of the most intriguing real-world incidents of 2024: the XZ backdoor — a stealthy supply chain compromise that could have impacted countless Linux systems worldwide.

This blog post walks through how we applied ACH to evaluate which threat actor group was most likely behind the attack, based on available TTPs, motivation, and behavioral alignment.

🔍 The Problem Objective: Determine which threat actor group was responsible for embedding the XZ backdoor.

We framed the investigation around three guiding questions:

Who has the capability and motivation to execute such an attack?

What specific Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) were used?

How well do these TTPs align with known threat actor profiles?

🧠 Hypotheses We considered several possibilities — some more likely than others:

Hypothesis A: The backdoor was added by mistake (Jia Tan was not malicious).

Hypothesis B: Jia Tan acted alone, with no ties to a known group.

Hypothesis C: The attack was launched by APT 29 (Russia).

Hypothesis D: The Lazarus Group (North Korea) was responsible.

Hypothesis E: APT 41 (China) executed the attack.

Hypothesis F: The United States did it (unlikely to be publicly provable).

Hypothesis G: An unknown, emerging threat actor was behind the breach.

📚 Evidence Collected We then gathered evidence, including:

Use of command & control tactics and custom infrastructure

Unusual patience and community trust-building (over years)

Surgical, quiet, non-monetized operation — pointing toward espionage

Backdoor access to sensitive systems, but no immediate use (a “prepare the battlefield” approach)

Focus on supply chain compromise, not direct targets

Use of developer tools instead of traditional malware payloads

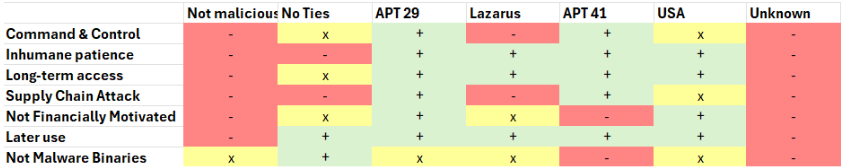

🧮 The Matrix and Sensitivity Analysis Using ACH, we built a hypothesis matrix to cross-check evidence against possible actors. APT 29 stood out — matching not only the tactics, but also the strategic objectives of long-term, stealthy espionage.

Even when testing for bias (e.g., questioning if it was truly a supply chain attack), APT 29’s history with lightweight implants, living-off-the-land techniques, and espionage-focused motivations still aligned the best.

✅ Final Assessment After evaluating the evidence, APT 29 emerged as the most likely actor. While absolute certainty is impossible (especially in cyber attribution), the ACH framework helped us reason through multiple perspectives and avoid confirmation bias.

💡 Reflection This exercise emphasized just how layered and complex attribution can be in cybersecurity. ACH provided a structured way to cut through assumptions and anchor our analysis in evidence. With more attacks leveraging open-source and supply chain vectors, structured analytical techniques like ACH will only become more critical for defenders.